Weekly Forecasts 24/2025

Forecasts for U.S. private investments and real GDP + Summer Offer

Forecasts

The analysis of real gross private domestic investments and real gross domestic product of the U.S.

Forecasts for U.S. investments and economic growth

This week we decided to take up forecasting an entirely new set of variables: the real gross private domestic investments and the real GDP of the United States. This is partly because we need to incorporate more sophisticated models for forecasting Chinese bank lending, leading indicators, and U.S. bank lending, which takes time. We detail the issues we encountered with these time series in the June Black Swan Outlook. Other reasons to start to forecast U.S. investments and GDP are the need to update our GDP forecasting model and simply the need to understand the direction of the U.S. economy in a more profound manner.

The two variables are naturally highly co-dependent. This is visible also in their statistical analyses, which are based on a cointegration relationship existing between the variables. The forecasts our model yielded were interesting, to say the least. They imply that the U.S. economy would be heading into a rapid acceleration followed by a deep slump next year. The forecasts of U.S. real GDP and real GPDI thus mirror those of leading indicators, which also implied that the world economy would be heading into an acceleration before entering into a slump next year.

Today we also launch our traditional summer campaign. This year we offer the annual subscription to the GnS Economics Newsletter with 25% off. The offer runs until 7 July, and I urge you to claim it by subscribing below.

Tuomas

The impulse-response analysis

As is already customary, we first run impulse-response analysis to establish some form of statistical causality between the (seasonally adjusted) U.S. Real Gross Private Domestic Investment (RGPDI) and (seasonally adjusted) Real Gross Domestic Product (RGDP).1 It can be assumed that the two variables have a jointly causal relationship, implying that they affect each other. This is because it can be assumed that the private investments and GDP are driven by the same underlying stochastic process. What we mean by this is that a very complex network of decisions of individuals, corporations, and governments (political leaders and civil servants) is driving both series. Economic growth is also essentially driven by the growth in productivity, as explained by Tuomas earlier this week. Productivity cannot grow without investments. Hence, investments and economic growth are inherently bound and likely to be driven by the same stochastic process.

Therefore, because the processes that create domestic private investments and GDP are so complex, we can assume that the tests will find that both are driven by cointegrated stochastic trends. The tests we use imply that both series are I(1) nonstationary and that they share one cointegration relationship, implying that they are driven by the same stochastic trend. This is how their time series looks.

The figure does not show the U.S. recession periods, but if we look at the 2000s, we can see noticeable dips in the series of real gross private domestic investments in 2000 (the dot-com recession), in 2009 (the Great Financial Crisis), and in 2020 (Corona lockdowns) in excess of those visible in the real GDP series. We can thus assess that the real private investment series is more sensitive to recessions than the real GDP series. This makes sense, because consumers and corporations tend to cut all spending when an economic downturn appears, which naturally accelerates the decline of the economy. When they recover, the economy recovers. This is why we can also assume that the real gross private domestic investment series leads the two.

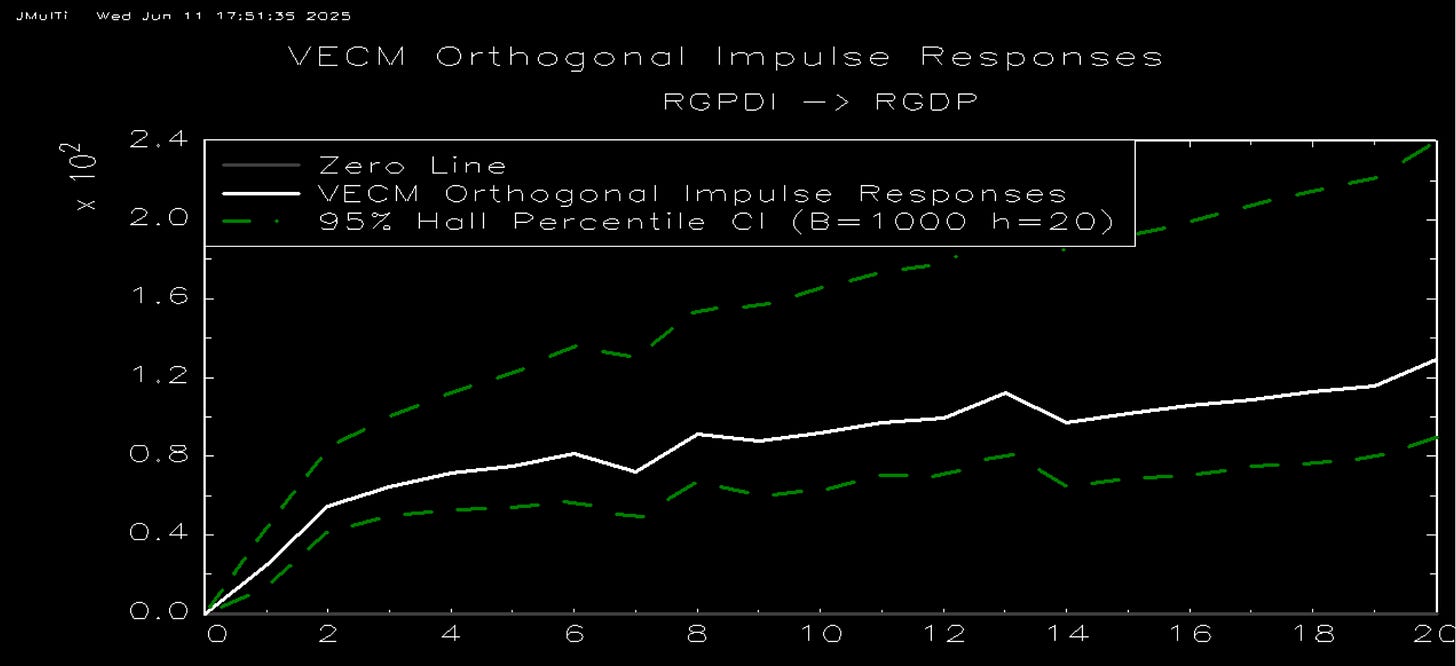

To find out, we estimated a Vector Error Correction (VECM) model assuming one cointegration relationship to exist between real GDP and real GPDI. This is also what the Johansen Trace Test indicated. That is, the test indicated that there exists one (stationary) linear combination between the time series of real GDP and real GPDI. After our model checked out (while there was heteroscedasticity present; see below), we estimated the orthogonal impulse-response functions between the variables, where 95% confidence intervals were bootstrapped with 1000 replications. Here are the impulse-response functions between real GDP and real GPDI.

As speculated above, a shock to the real GPDI leads to a permanent-looking and even growing response in the real GDP of the U.S. Another way to put this is that any changes in gross private domestic investments, whether positive or negative, have a long-lasting or even permanent effect on the U.S. economy (for better or for worse). This is a central feature of stochastic trend processes. That is, the stochastic trend processes are said to have an infinite memory, where all shocks or innovations are permanent to the system. Just consider the effect of a major technological innovation on the economy like, for example, computing. The first investment bringing computers into productive use delivered a permanent (positive) shock to the economy. The same happened with the invention of the internet, industrial robots, and AI. All of them had a permanent effect on how households and corporations operate and how productive they are. The stochastic trend process behind private investments and thus GDP, consisting of investment and consumption decisions made by a vast number of actors, was permanently altered as a result. This is one way to explain what we observed above with the impulse-responses.

Here is what happens when we change the roles.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to GnS Economics Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.