Due to the massive vulnerabilities created by governments and central banks over the past 12 years, we are not threated by just an energy and inflation crises, but a series of over-lapping crises.

Energy crisis came to be because of the Russo-Ukrainian war and a series of poor political decisions, especially in Europe, during the past 30 years. Now, they are backfiring rather massively.

We have documented the effects of the war in several of our previous posts and outlooks, but we have not really explained, where all these developments (corona, lockdowns, war and sanctions) are likely to lead us to. They are brewing a “mother of all economic crises”, which may erupt as early as this winter.

This ‘multifaceted economic crisis’ is likely to include:

Inflation crisis (already here).

A financial crash.

Banking crisis.

Sovereign debt crisis.

Corporate debt crisis.

Currency crisis.

Needless to say, that we have never, in all of known history, experienced such a ‘perfect storm’. In this entry, we explain the characteristic of each crisis, except the banking crisis, which we have detailed already before.

Inflation crisis

Inflation crises can have two meanings. It can either be used to describe a period of rapid and/or unsustainably rapid inflation, i.e., hyperinflation.

In each case, periods of very rapid increases in consumer prices usually result from the monetization of government deficits. During monetizations, fiscal agencies determine the real government budget deficit that the central bank must finance. Central banks cover this with seigniorage revenue by expanding the monetary base, and the rate of money growth determines in turn the equilibrium rate of inflation. This is especially true for periods of hyperinflation, when the monthly inflation rate exceeds 50 percent.

However, periods of high inflation can also result from indirect financing of government deficits through interest rate targets for government bonds and/or asset purchases by the central banks, or programs of quantitative easing. This is essentially what has now happened, and the coronavirus and Russo-Ukrainian war have been just triggers for the inflation crisis.

Currently, two of the main drivers of fast or even runaway inflation (hyperinflation) have started to emerge:

1) Excessive money in circulation.

2) A broad reduction in productive capacity

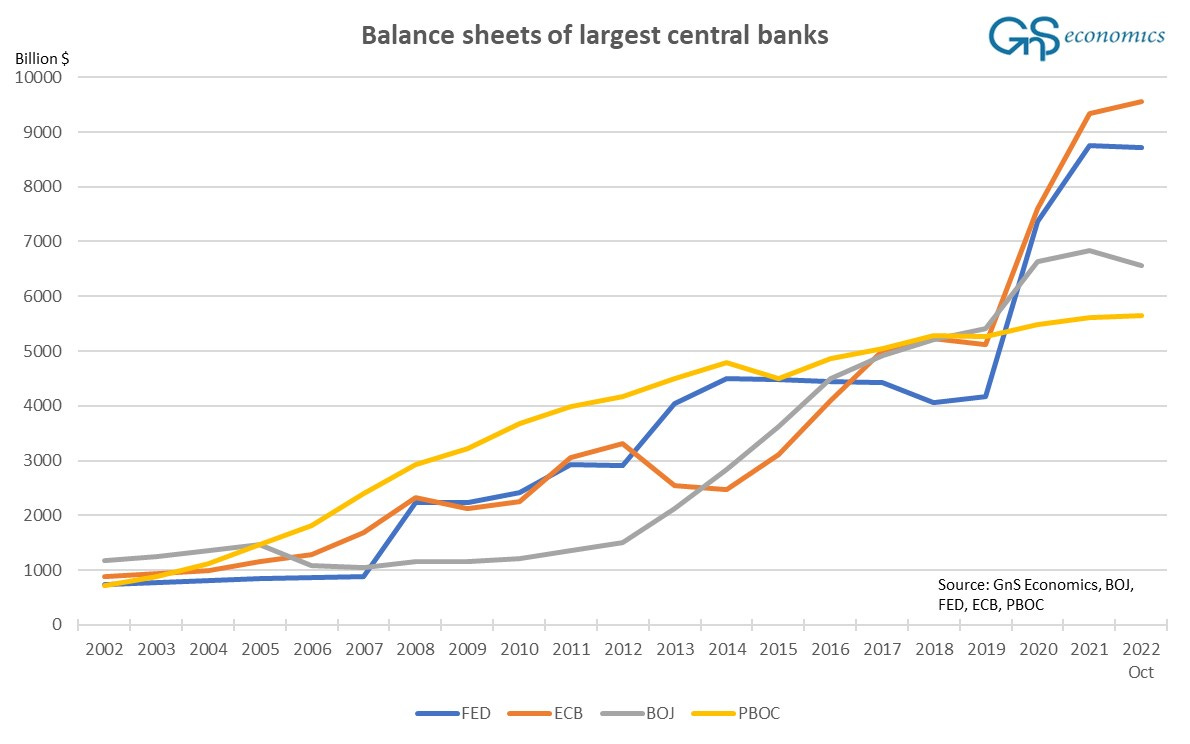

The balance sheets of central banks have swollen most especially over the past year due to the aforementioned QE programs.

A QE program is essentially a credit line of the central bank. Using it, the central bank buys an asset, usually a government or corporate bond, from investors through one of several Primary Dealer banks.1 It thus creates money in the process of buying the bond, which leads to an increase in the money supply. Fortunately, the Fed has started to diminish its balance sheet thus drawing (artificial) liquidity from the markets, but this will lead to another set of problems (see, e.g., this and this).

In any case, the amount of newly created money sloshing around in the global economy is massive.

Production capacities may be hampered by forces that push companies into bankruptcy. One of the most historically common and pernicious is war, such as the Great War which contributed to the hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic between 1919-1924, or the economic crash caused by the collapse of the ruling Communist political system, which preceded the Russian hyperinflation in the early 1990s. Currently, production capacities and supply-chains are under strain due to the war and (especially) sanctions related to the war.

Moreover, production capacities can also collapse due to the large-scale failure of ‘zombified’ corporations driven by, e.g., rising interest rates. Thus, counterintuitively, rising interest rates may actually push us into a hyperinflation, although this scenario is a bit “theoretical”, at least for now.

Currency crisis

Generally, a currency crisis is an attack on the exchange value of the currency in the markets. If the exchange rate is fixed or pegged, such an attack will test the monetary authorities, that is, the central bank's commitment to the peg.

Market participants expect that the policy of monetary authorities will be inconsistent with the peg, and they will try to force authorities to abandon the peg thereby validating their expectations. What matters for speculators are the internal economic conditions relative to the external conditions set for the currency. If these are incompatible in some meaningful aspect, monetary authorities face a trade-off between external and domestic goals for exchange rates. In these circumstances, random shocks in the foreign exchange markets, called sunspots, can trigger an attack on the external value of the currency.

We have already seen sudden collapses of currencies of former save havens, i.e., Japan and the United Kingdom. They show that there’s a point, for every country, where the trust to the public finances is broken and the investors start to flee the country creating both a sudden spike in the sovereign yields and collapse of the fx-value of currencies. In both cases, the central bank was forced to step in to provide support for the sovereign debt and currency markets.

Yet, the breakup of the Eurozone is probably the biggest ‘tail-risk’ in considering currency crises, currently. A breakup of the common currency would mean that all sovereign debt would be subject to possible redenomination in new national currencies under the Lex Monetae, or the ‘Law of Money’.

This specifies that a sovereign state has the right to regulate its currency under international law. Therefore, the creation and substitution of the national unit of payment is entitled to recognition by other countries including their courts and official bodies. This means that sovereign states can dictate the currency they use in debt repayments.

However, some national debt currently carries the Collective Action Clause, CAC, which means that they must remain in the euro.2 However, if the euro is dismantled in totality, the redenomination will be decided by negotiations between the government and investors. In this case, it is impossible to predict in which currency principal and interest payments on the bond will eventually be made.

The foreign exchange rate of a currency can crash even if the rate is not pegged. During a currency crisis, the external value of a domestic currency decreases, which leads to an increase in the value of foreign debt, leading possibly to a corporate and/or a sovereign debt crisis.

Sovereign debt crisis

Sovereign debt or fiscal crises consist of periods of severe deficits in public financing and/or periods during which the government fails to meet domestic or foreign obligations.

Gerling et al. (2017) identify a fiscal crisis by four criteria: credit event (foreign default), implicit domestic default (monetization, domestic arrears), loss of market access and exceptional official financing (IMF). In a credit event, the government of a country announces that it will not pay interest and/or the principal of some or all of its debt (bonds) that it owes to foreign creditors. This means that the government defaults on its foreign-held debt. This usually leads to loss of access to international money markets, which may also happen if the interest rates on sovereign debt rise so high that they become impossible for the government to service.

The concept of monetization was explained above. The government can also default on debt held by its citizens and domestic institutions. In this case, the government defaults on domestically-held debt. This may have serious repercussions for the banking sector of a country, which usually holds domestic sovereign bonds as collateral possibly leading to a banking crisis.

IMF programs were originally constructed to help countries during balance-of-payment crises. In time, and especially after the fall of the Soviet Union, the IMF was forced to change its role quite drastically and diversify its portfolio of lending. Countries apply to IMF programs mostly because they provide emergency funding, technical and financial assistance and enforce unpopular but often necessary economic reforms during crises.

The key drawback to an IMF program are the conditionalities attached to them. These include removal of price controls from state economic enterprises (SEEs) and removal of subsidies. During the onset of the program, there are almost always agreements regarding ceilings for fiscal deficits and domestic credit. These lead to austerity. In addition, public and private debts are often rescheduled, and the nominal exchange rate regime is changed.

Corporate debt crisis

A corporate debt crisis does not have a clear definition in the academic literature, but it can be considered as a situation where a large group of corporations are unable to make ends meet, implying that they will default on their debts. This will usually translate into a banking crisis, as banks tend to hold large quantities of loans to corporations. And should corporations default on their debt, banks will suffer crippling losses.

This is a major risk now, as the global economy is likely to be infested by hordes of ‘zombified’ corporations surviving on cheap (and plentifully available) funding alone, which is now disappearing. A corporate debt crisis usually turns into a fiscal and unemployment crisis as the ability of corporations to pay taxes and salaries, and provide employment, declines.

Coexistence of crises

As briefly described above, economic crises have a tendency to coexist. Inflation crises can lead to a recession, i.e., to a stagflation. Higher input costs and declining demand will lead to corporate losses, which will in turn lead to bank losses. Rising interest rates may further hasten this development crushing corporate and household sectors. The end-result is a corporate debt crisis and a banking crisis.

Currency crises can also lead to bank losses and high inflation through devaluation and further to a debt crisis, as the principal and interests of a foreign-currency-denominated loans will increase. Banks may have contracts (e.g., loans, bond holdings) in foreign currency; a devaluation of the external value of the currency will cause the cost of these contracts to become more burdensome. This would have a highly detrimental effect on corporations holding large amounts of foreign currency denominated debt.

If a country is highly dependent on foreign commodities, devaluation may increase their prices, causing inflation to peak. On the other hand, a corporate debt crisis can put in motion a banking crisis leading to a crash in the value of a currency causing a sudden rise in foreign currency denominated sovereign debt.

A withdrawal of monetary support (quantitative tightening and/or interest rate hikes) in an extremely-levered market environment, like now, is likely to lead to crash in the asset and credit markets leading eventually to both a banking and corporate debt crisis, a currency crash and even further to a sovereign debt crisis, when an over-indebted government succumbs to the rising yields and the combined effects of the crisis. This almost happened to Britain in late September. Alas, crises often coexist when there’s too much debt in the economy and something triggers the fall.

Now we are in such a situation where the crises can occur in a sequential—or even overlapping manner. The coronavirus (lockdowns) and war-related costs are only triggers. The main drivers of the global economic collapse are the massive imbalances build into the global economic and financial systems, and the over-indebtedness of both government and corporations, which we have been warning about for over five years.

This is an exceptional situation, which is why preparation must be equally exceptional. We will return to it in our next preparation post.

A bank is called a ’Primary Dealer’, when it’s permitted to deal directly with the government and/or the central bank.

In the midst of the euro-area crisis, the 24-25 March 2011 European Council meeting decided to Include CACs in all new euro-area sovereign bonds with a maturity of more than one year, from July 2013 on. The CACs would be identical and standardized for all euro-area Member States; furthermore, they would be based on the CACs that are commonly used in the US and the UK Markets and are governed by the two countries' respective laws.

These CACs were developed and agreed by the EFC in November 2011 and were subsequently

included in the ESM Treaty (Article 12(3)). This 'euro area model CAC 2012' relies on a 'two-limb' voting structure. Specifically, a minimum threshold of support must be reached both in each bond Series (66⅔ % of the outstanding principal) and across all series subject to the restructuring (75 % of the outstanding principal).

In the opinion of Sami Miettinen, an investment banker familiar with bondholder restructurings, a 75% voting group acting in cooperation with the issuing nation can also change the redenomination of the bonds from the euro to some newly created domestic currency.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk. Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

"Production capacities may be hampered by forces that push companies into bankruptcy."

I'm afraid the whole chapter "Inflation Crisis" of this document worth reviewing once again. BR JKi