From Tuomas Malinen’s Forecasting Newsletter.

Within a week, from October 23 to October 29, the Great Crash annihilated 29% of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), but the worst was still to come. From the peak (3 September, 1929) to through (8 July, 1932) the DJIA fell by over 89%. The Great Depression that followed all but decimated the wealth of both the rich and poor who had invested in the stock market. But, what was the Great Depression and how it came to be?

The Great Depression was one the deepest economic contractions in the modern era. It concentrated on the economies of the U.S. and Europe but its repercussions were felt globally. The countries involved accounted for over 55% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP). The Great Depression rivals with the Long Depression of the late 1800s as the most severe economic contraction of the U.S. It started from the stock market crash in October 1929 and morphed into a global banking crisis a year later.

The immediate aftermath of the Great Crash was relatively controlled, however. The Fed provided amble reserves to New York banks which supported the brokerages which in turn supported the markets. The economy even seemed to stabilize through the year-end. The ‘Great Contraction’ did thus not start right after the crash, although it struck a serious blow to the psyche of the households, corporations and investors, deepening the economic contraction, which had started in August 1929. Consumption never recovered from the crash, but continued to fall in 1930.

The “humble” beginnings: Domestic bank failures

There were two main forces that drove the Great Contraction: deepening economic slowdown and bank failures. Moreover, while the depression did not start right after the stock market crash, it played a role.

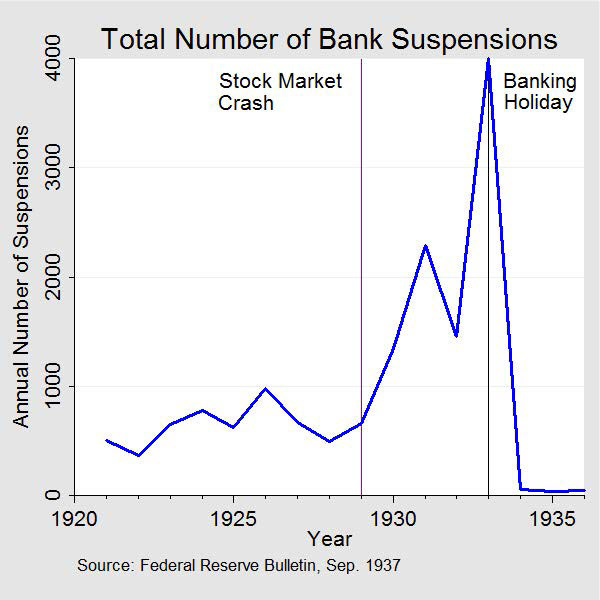

There was a brief hope for a recovery in 1930, but then the banking crisis started with the failure of Caldwell and Company, a financial holding conglomerate headquarted in Nashville Tennessee in November 1930. At this point, the economic contraction had lasted for 15 months, and a recovery was expected. The parent company of Caldwell and Company got into trouble after its owners, especially its founder Rogers C. Caldwell, lost substantial sums of money in the stock market crash. The company was already in trouble, because it had not followed standard financial and business practices, and had taken heavy risks, and the stock market crash was the last nail in its coffin. To cover the losses owners drew cash from other corporations they were controlling. Then on November 7, the Bank of Tennessee in Nashville was audited by state examiners, who declared it insolvent. This led to an imminent collapse of Caldwell and Company causing a run on its affiliate banks in Knoxville, Tennessee, and in Louisville, Kentucky, on November 12 and 17. These led to cascading bank runs and failures of commercial banks in Arkansas, Kentucky and Tennessee. On November 14, 1930, Caldwell and Company went into receivership.

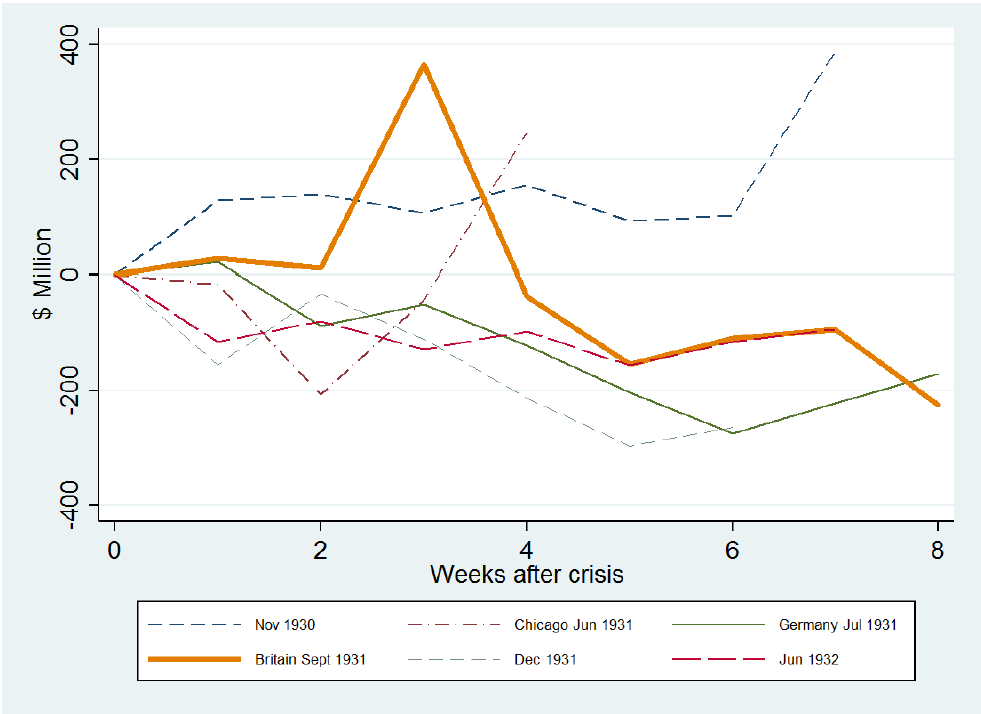

The rate of bank failures eased in early 1931, which led to a short-lived revival of the US economy in the first half of 1931, before Chicago was hit by her first banking panic in June 1931. Then the crisis went global. The U.S., and many other nations, actually experienced several waves of bank runs, depicted in this figure.

The crisis goes global

In November 1930, possibly influenced by the failures related to Caldwell and Company, French depositors started to withdraw funds from commercial banks across the country transferring them into savings institutions (Caisses d’épargne).1 Runs began from Banque Adam, a regional lender in the north of France, which failed on November 5. The failure of this well-establish bank sowed seeds of mistrust and ignited bank runs across the country, which hit banks both big and small. The runs lasted till December but banks continued to fail until April of 1931.

On May 11, 1931, a large Austrian regional lender, Credit Anstalt, informed it had lost half of its capital. Austrian law required that a bank, which had lost half of its capital must be declared bankrupt. On the following day, the Austrian government announced a 160 million shilling bailout for Credit Anstalt. This was not nearly enough, and on May 29 the recently established Bank of International Settlements arranged additional credit line of 100 million schillings for the bank. These actions, however, did not stop the bleeding, and on June 27 the Austrian government, with a federal budget of 1800 million schillings, covered the liabilities of Credit Anstalt, which at that time stood at 1200 million schillings. This led to an outflow of Austrian foreign reserves forcing the issuance of exchange controls on October 9, 1931. Credit Anstalt was taken over by the Austrian government and on May 5, 1934, the Austrian schilling was devalued by 28% which stopped the outflow of Austrian assets.

Credit Anstalt had been both growing and suffering through forced mergers with near-failed banks, like Bodencreditanstalt, and hyperinflation of 1923-24,2 which had left it severely under-capitalized. The bank operated in the area of the former Austro-Hungarian empire lending to its successor states, using short-term funds borrowed mostly from the U.K. and the U.S. The bank started to falter in 1930, because of of global recession, which had started in Germany and the U.S. 1928 and 1929, respectively. Loans losses mounted and when the short-term funding from the U.S. dried up during the winter of 1930/-31, the bank was forced to acknowledge its gargantuan losses.

The collapse of Credit Anstalt triggered a run on Austrian banks followed by runs on Hungarian, Czech, Romanian, Polish and German banks. The German financial crisis was ultimately responsible for turning the global recession into a depression.

Germany's economy and banking sector had struggled since the hyperinflation, and due to the harsh war reparations demanded especially by France. Ravaging inflation, political miscalculations and failure of the creditor countries to admit the dire economic situation in Germany, had left German banks severely under-capitalized. When the U.S. capital flows in the country dried up in 1928, Germany choose to deflate despite her economy already experiencing a downturn. Soon the country was in the grips of mounting unemployment and social unrest. These led to a full-blown run on Germany's banking sector in Summer 1931 due to the collapse, and bailout, of Credit Anstalt. In July 1931, the crisis in Germany truly got going with the failure of a major German lender Danatbank. Germany received no sufficient assistance from the surplus countries (i.e., France and the U.S.), and in August 1931 she abandoned the gold standard, enacted exchange rate controls (but her currency was not devalued) and halted the free flow of gold and capital. These delivered a major shock to the European financial system.3

The second leg of bank runs started in France in September with problems in some banks, like the Banque Nationale du Crédit (BNC), a national lender, emerging already in July. The bank was hit by a severe bank run and lost half of its deposits after the Sterling shock in September (see below), forcing the French government to bail her out. The global recession had hit France hard, and by Summer of 1931 French banks were suffering from rapidly growing non-performing loans and failures of firms. A fear of contagion set in, leading also healthy banks to face runs. The depositor runs and bank failures lasted till the spring of 1932. Moreover, France had fixed her exchange rate very low providing her a competitive advantage. This led to notable influx of gold into the country, which the Banque de France immediately sterilized.4 This inflow of gold into France, and the U.S., between 1927 and 1932 and its sterilization by respective central banks exported deflation across the world, because it diminished reserves in the global financial system.

On September 21, 1931, this deflationary process came to an abrupt end, when large withdrawals of money from London forced the British government to break the link between pound and gold. The pound quickly depreciated by 30% against the US dollar. This meant that currencies of countries who had tied their currencies to pound also fell. The gold bloc of Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland started buying gold with US dollars, which reduced the reserves in US banks. Depreciation of the British pound and the decline in bank reserves exported deflation to the U.S. pushing her economy into a depression.

Essentially, the U.S. and the global banking system were hit by three shocks, in consecutive manner, during the Summer of 1931. First, there was a bank run in Chicago in June, then a German banking crisis and capital controls in July and in August and, finally, the U.K. severing the gold standard in September. These acted as a deepening shock within the U.S. banking system. While the run in the mid-western states in November 1930 and the banking panic of Chicago in June 1931 led to deposits fleeing into banks in New York City, basically every shock after the German banking crisis in July 1931 led to cash withdrawals (i.e., to liquidation of deposits).This can be seen as a shift from regional banking crises within the U.S. to a nationwide bank run eventually turning the depression of the 1930s into something deserving the name “Great”.

Banking panics eased in early 1932 only to accelerate again from June 1932 on. The Great Depression reached its climax in a national banking panic in early 1933.

The Great Depression

The Federal Reserve made some cataclysmic mistakes in handling the crisis. It stubbornly defended the gold standard and raised interest rates in late 1931 and tightened money supply during the winter of 1932-33. These policy mistakes seriously hurt the ailing banking sector escalating both the bank failures and the deflation cycle.

Other policy mistakes were also made. The Smoot-Hawley bill, signed into law in June 1930 despite signed opposition by 1038 American economists, also exacerbated the global reach of the contraction. The bill raised US import duties leading to retaliatory action around the world. The legislation thus introduced a trade war to burden the global economic situation even further.

While monetary and fiscal policies could have been used to combat declining output and rising unemployment, they were mostly designed to defend the gold standard. If exchange rate adjustments would have been allowed to remove the imbalances between countries and if debtor countries would not have been forced to confront balance-of-payments and debt repayment problems caused the draining of the dollar liquidity, the depression could have been much shallower and not so far-reaching. But the gold standard, and very selfish policy choices, made this method of stabilization impossible. There was also a strong held view among some in the government that banks should be allowed to fail and the 'excess' to be removed from the economy. Andrew Mellon, who acted as a US Treasury Secretary from 1921 till 1932, stated "liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate [...] It will purge the rottenness out of the system". The fact also is that the U.S. entered the 1930's with a weak, under-capitalized banking system, which relied on unit rather than branch banking. Because individual banks did not have support of a larger branch, they failed en masse. When banks and brokerages failed, credit started to contract and demand slumped.

Despite of these mistakes, the economic contraction could have stopped in 1931, or it at least could have remained shallower, if the banking crisis would not have gone global. The banking crisis going global, the gold standard and policy failures of both central banks and politicians morphed the recession into a global depression.

In the US, a vicious loop of deflation and bank failures developed. As businesses started failing, their inventories were sold to the market, which dumped prices reducing the net worth of other firms in the same industrial sector. Business failures led to loan losses, which made banks more reluctant to lend with some banks failing. With less credit available, fewer firms were able to roll over their debts bankrupting them. Their inventories were sold, prices fell, demand slumped, banks failed and credit diminished which pushed the reinforcing loop of economic calamity and deflation onwards.

The US economy finally bottomed out during the General Bank Holiday in March 1933 helped by the depreciation of the dollar. However, mid-west and southern states of the US continued to suffer for several years, with the Dust Bowl, i.e., dust storms ravaging the southern plains of the U.S. between 1930 and 1939, contributing to this.

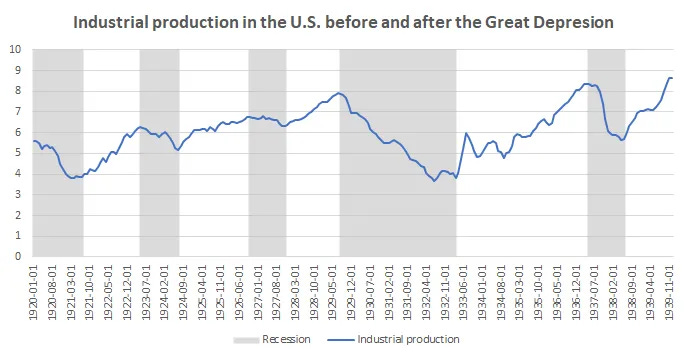

From the peak of the economic expansion in August 1929 through March 1933, the U.S. industrial output fell by 52%, wholesale prices fell by 38% and real income by 35%. Over 9800 banks (nearly 40% of the total) failed in the U.S. between 1929 and 1934. It was an utter economic calamity,5 and did not stop there with the U.S. experiencing a deep economic contraction in 1937-38.

Conclusions

To summarize, there were five main components, which turned the Roaring Twenties and the Crash of 1929 into the Great Depression:

Several waves of bank failures hitting the US, which led to a financial paralysis and to a fall in the monetary stock.

A raise of the US import duties in 1930 and some other protectionist policies which led to an decline of the world trade.

A monetary tightening by the Fed in late 1931 and during the winter of 1932-33, and its inability to act as a ‘lender of last resort’ to banks especially during the early stages of the banking crisis (1930-31).

The financial collapse of Austria and Germany during the Summer of 1931.

The gold standard aggravating the deflation and transmitting the crisis across the globe.

While many researchers do not attribute the onset of the Great Depression to the Great Crash in October 1929, the collapse of the stock markets played a crucial role in the failures of the banks tied to the Caldwell and Company in November 1930. The likely (possible) contagion from the banking crisis in the mid-West to French banks also made the crisis global from. These at least make the Great Crash and Great Depression tightly related, if not more.

The obvious lack of global co-ordination in handling the crisis as well as central banks not providing a credible liquidity backstop for banks in early stages of the crisis were also crucial in turning the global recession into a depression. The gold standard was a clear, and detrimental, ‘transmission mechanism’ transmitting the deflation between the U.S. and Europe. The selfish policies of France and the U.S. concerning gold inflows exported deflation and essentially pushed the crisis from country to country. Moreover, if Germany would have been treated more leniently after World War I, there would probably not have been a hyperinflation leading into the global banking crisis and to the rise of the Nazi party, who gained most their momentum from the hyperinflation and the economic depression.

Yet, the role of the Federal Reserve in creating, and in deepening, the crisis is also unquestionable. It fueled the speculation in the 1920s by keeping rates artificially low regardless of the strong inflows of gold into the U.S. It tightened too late which, somewhat counterintuitively, fueled the speculation by drawing more funds from abroad into the U.S. Probably the biggest mistakes were the decision to rise rates, to defend the gold standard, in September 1931, and to sterilize flows of gold during the winter of 1932-33 leading to the decline in the ‘Fed credit’, i.e., decline in the money supply from the central bank. This is the likely main reason behind the national bank run in early 1933.

The banking crises and deflation in the U.S. were finally halted by the national bank holiday, enacted by President Roosevelt, lasting from March 6 till March 10 1933, the pledge of the Federal Reserve to cover all cash withdrawals from banks that re-opened, capital injections from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), and the passing of the Banking Act, or the Glass-Steagal Act, on June 16. The act delivered three major changes to the U.S. banking system:

It prohibited commercial banks from underwriting or otherwise dealing in corporate securities;

It imposed limits on the interest rates commercial banks could pay on deposits;

And, most importantly, the Act established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, or FDIC, compelling all Federal Reserve member banks to take part in the (national) deposit insurance scheme.

These measures returned the trust to the banking system, ending the runs. As a result a turning point in the economy appeared during the latter part of 1933, while an actual economic recovery took over year to materialize (see, e.g., the development of industrial production in the first figure).

However, we have to remember the flip-side of the Great Depression, and all great crises. People who were able to take advantage on the heavily deflated prices, made fortunes during the years of economic recovery that followed the economic malaise. This massive economic crisis thus turned out to be a great opportunity to those, who were able to navigate through it fearlessly and efficiently.

Most of the economic data and quotes are from Lessons from the 1930s Great Depression by Nicholas Crafts and Peter Fearon.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

The savings institutions generally paid higher interest rates than banks, while providing almost the same services (no lending, though).

Hyperinflation simply destroys the value of local-currency assets of banks.

France and the U.S. should have let their currencies to appreciate to halt the inflow of gold, or to let money supply in the country to grow, which would have provided demand and supported imports and global demand. However, with gold standard there was (almost) always a sterilization, not appreciation (of the currency). Also, when gold reserves were drawn from a country, there was (almost) always deflation, not depreciation.

As explained in the first entry, a central bank sterilizes by letting the ratio of gold reserves to notes in circulation to increase or it can rise the interest rate to tighten the supply of short-term credit. Outflows of gold naturally have an opposite effect diminishing the amount of money in circulation, unless interest rates or ratio of gold reserves to notes are lowered.

These figures, from Lesson from the 1930s Great Depression, provide some additional information on the depth of the contraction:

Gross private domestic investment, measured in constant prices, had reached $16.2 billion in 1929; the 1933 total was only $0.3 billion. In 1926, gross expenditure on new private residential construction was $4,920m; in 1933 the figure had fallen to a paltry $290m. Consumer expenditure at constant prices fell from $79.0 billion in 1929 to $64.6 billion in 1933. Durables were especially affected; in 1929, 4.5m passenger vehicles rolled off assembly lines; in 1932, 1.1m cars were produced by a workforce that had been halved.