In 2017, we discovered that 1) China had been the main engine of the world economy since around 2009, and that 2) her economy had become heavily over-indebted in the process. This led us to publish a series of warnings (see, e.g., this and this).

In early January 2020, right before the spread of the Corona virus out of Wuhan (see our warning at the end of January 2020), we noted that the ‘Chinese miracle’ has come to an end. However, lockdowns and massive stimulus carried the Chinese economy for three more years, but now Chinese growth-model has reached its limits, which carries a dire warning for the global economy.

China reported a drastic 14.5% (YoY) drop in exports in July, which is the deepest decline since February 2020, and the third consecutive month of declining exports. Notably, during the past three months China has seen a larger drop in exports than in November-January 2022/-23, when Europe, and the world, were in the grips of an energy crisis. This implies that the world economy is slowing down drastically, like we warned in June.

Yesterday, Rebecca Choong Wilkins, a Bloomberg economic correspondent in China, published a Twitter (X) thread going through the stress experienced by China’s local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs. There were also a very rare bankruptcy claim raised against two LGFVs in Guizhou (by Zhongtai Trust), which implies that creditors (holders of LGFV bonds) are becoming very anxious.

The problems of LGFVs are a dire omen for the Chinese economy, because they carry a very large pile of debt. They were the main tools through which Beijing run a massive, yet largely hidden economic stimulus in 2015/2016, which amassed a massive amount of ‘hidden debt’, not shown in official (government or banking) debt statistics. In February, the IMF estimated that there was RMB66.0 trillion (around 9.1 trillion USD) hidden debt in China’s LGFVs.

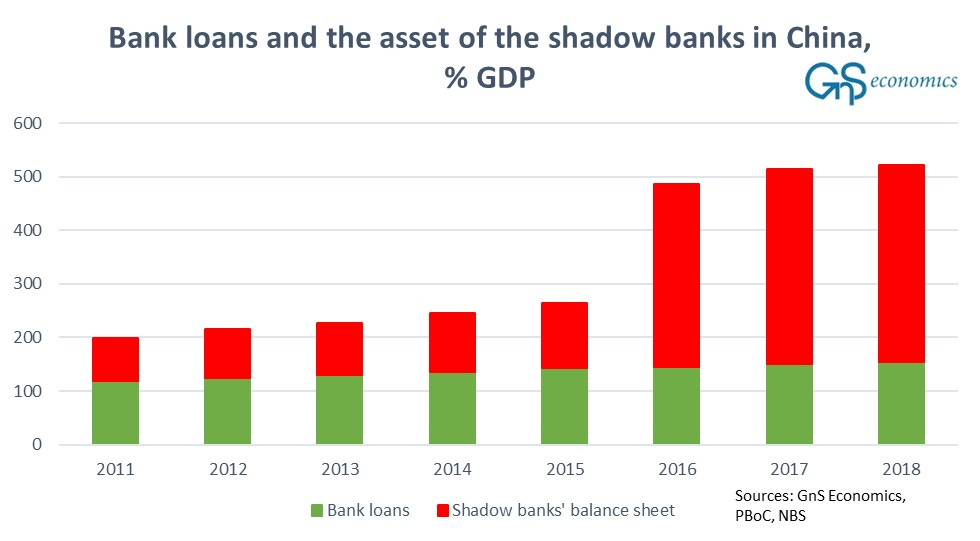

However, in late 2018, the People’s Bank of China estimated that the total amount of assets of shadow banks was over $50 trillion, which implies that the hidden debt in the Chinese economy is much larger. We discovered this in 2017, and in 2018 the situation in China’s shadow banking sector was already utterly unsustainable.

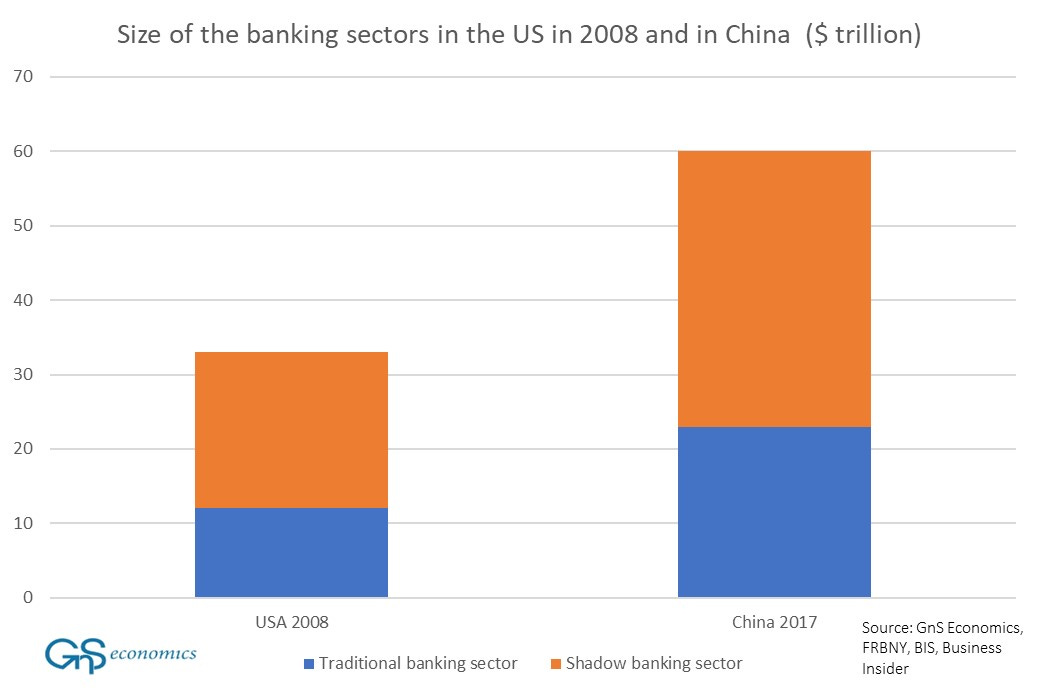

When we compare this to the ‘critical’ size of U.S. shadow banking sector right before the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, the severity of the situation in China’s economy becomes plainly obvious.

The problems of China’s LGFVs, and the shadow banking sector in general, has two (dire) implications:

The ability of Beijing to run (yet another) massive stimulus campaign has become severely hampered.

With massive China stimulus (á la 2009, 2016 and 2020) effectively off the table, the approaching global recession is likely to become much steeper than many anticipate.

This is not to say Beijing would not try to stimulate her economy once again, but like we saw in the spring, the effectiveness of further debt-stimulus is likely to be limited at best. This is because Chinese economy has, most likely, reached a point of debt saturation.1

We urge our customers to prepare for a drastic economic deceleration both in China and globally in the coming months.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. GnS Economics nor any of the authors cannot be held responsible for errors or omissions in the data presented. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor any of the authors cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

Like we explained in January 2019, this implies that any extended lending spree will lead to an impasse where households and companies will not—or cannot— absorb any more credit. Their need to meet their obligations forces them to start paying back debt. In a highly-levered economy, this means that the relentless rise in asset prices eventually halts, and then starts to decline—sometimes precipitously.