Commercial real estate (CRE) issues have been getting more attention this year, causing significant headaches for the banking sector and raising questions about the severity of the situation. Rising vacancy rates, the short maturity of loans, and the loans made during low-interest periods have all contributed to escalating the current predicament. We have written about this several times, and now we aim to explore the problem through the lens of bank balance sheets to determine which ones really suffer under this issue.

To begin with, CRE loans are occupying a large portion of the U.S. banking sector’s entire portfolio (Total Assets), standing at a significant 10%. CRE loans are also regarded as the most widely held loan type among banks, which is confirmed by the fact that the majority of banks (99%) have positive CRE loans. Basically, almost every bank in the U.S. is holding some type of CRE loan on their balance sheets. Therefore, it is no surprise that this is an area warranting close observation, especially because the risks posed by CRE exposure spread quite unevenly between large and small banks.

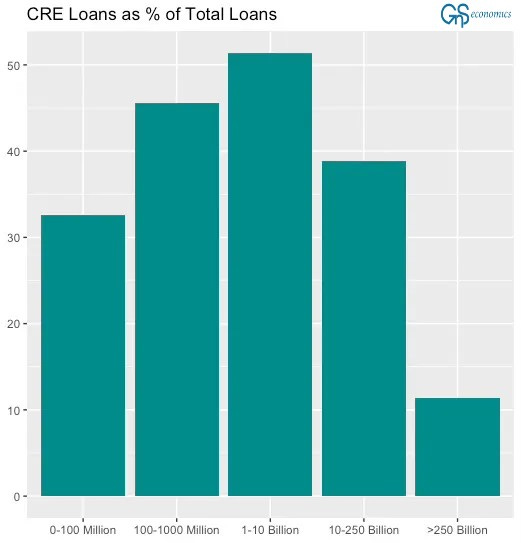

Figure 1 illustrates the average CRE concentration for banks based on their size, as a share of loans.

Community banks, which refer to small and medium sized banks, emerge as a primary source of concern due to their substantially higher exposure compared to their larger competitors. This is clearly visible in the figure, where, on average, these banks allocate 45% of their loans to CRE, while the largest banks maintain a more cautious concentration of around 12%. This difference is not unexpected, as community banks are inclined to take on more risks due to their lower capital requirements. This seemingly underscores the growing concerns surrounding community banks and their CRE portfolios, and this narrative is also heavily pushed by the media.

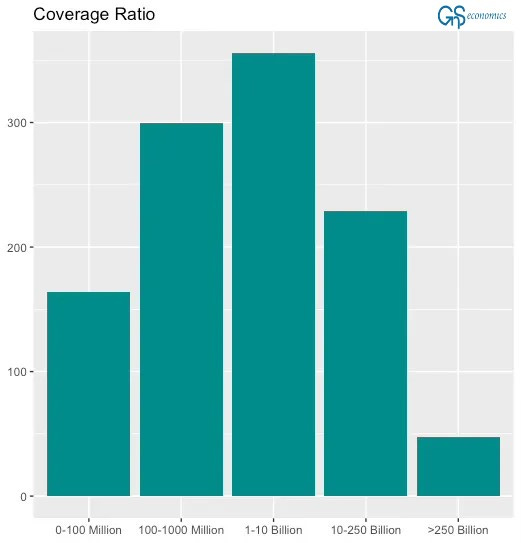

However, high CRE concentration alone do not inherently imply problems. The real issue arises from the combination of high concentrations, insufficient reserves, and delinquency issues. Therefore, it is essential to analyze the Coverage Ratio, which compares CRE to reserves for losses (Allowance for Loan Losses) plus Equity Capital.1 This ratio effectively measures the ‘leverage’ in the CRE portfolio. The higher the number, the higher the possible future risk.

Mid-sized banks are hovering at a Coverage Ratio of 300%, while the biggest banks maintain a modest 50%. This disparity seems to strengthen the argument that community banks are the primary issue. However, there is another side to the coin, when we examine Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) in CRE loans, they paint a different picture.

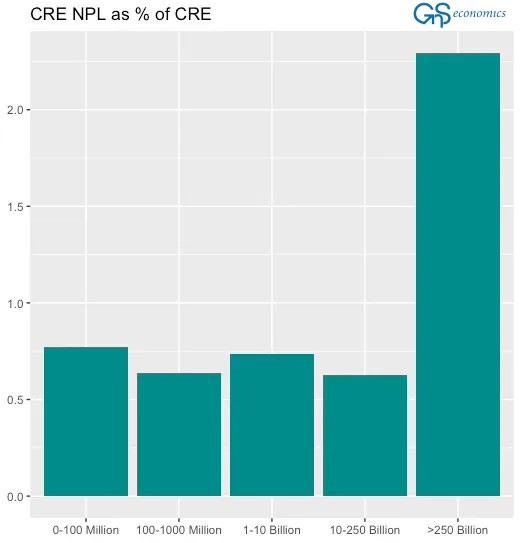

Non-Performing Loans are defined as loans that are either in non-accrual status or 90 days past due. The occurrence of NPLs is increasing across various bank portfolios, and the big banks are not excluded from this trend. The following figure presents the average CRE NPL percentage in CRE loans, categorized by the same bank sizes as previously analyzed.

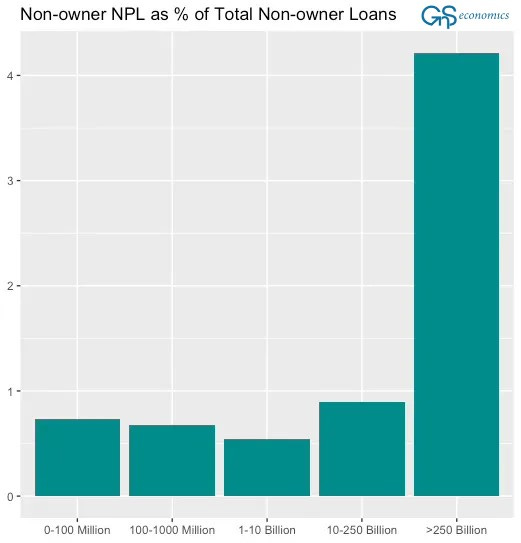

The biggest banks are definitely the ones which are having NPL issues at the moment, which is even more visible when we look at the Non-farm Nonresidential Non-owner occupied component of CRE. This component is crucial, because a CRE loan is classified as a Non-farm Nonresidential Non-owner occupied if the borrower is making payments primarily from rental income, hence this category is very sensitive to any issue in the sector.

NPLs in the Non-owner component have reached worryingly high levels among big banks, while for the remaining sector, it stands at normal levels for now. As the largest component of commercial real estate loans, the significant spikes in NPLs among big banks will undoubtedly worsen credit conditions in the already troubled CRE market.

Conclusions

The issues with CRE loans have been circulating for some time, but the narrative often focuses on community banks. However, as we observed, identifying the weak links in the banking sector is not straightforward. Small and medium banks undeniably have a higher exposure to commercial real estate (CRE) compared to large banks, but they also have lower levels of non-performing loans.

Nevertheless, the situation is expected to soon reveal its impact. Banks facing increasing problems will raise their provisions, negatively affecting their profitability and, more importantly, the credit market. Bank failures are almost certain to follow, as warned by the Chairman of the Fed, Jerome Powell. Buckle up!

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as an investment advice nor advice on the safety of banks. GnS Economics nor any of the authors cannot be held responsible for errors or omissions in the data presented. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment before making any investment decision or decision on banks they hold their money in. Readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor any of the authors cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

A coverage ratio broadly measures a company’s ability to service its debt and meet its financial obligations. In our case, we divided the total outstanding CRE loans by the sum of the Allowance for Loan Losses and Equity Capital. This ratio indicates the leverage of the CRE loans compared to all the reserves. Alternatively, the denominator and numerator can be reversed, showing how much of the total portfolio is reserved.