From Tuomas Malinen’s Forecasting Newsletter.

Issues contributed:

The U.S. banking sector is more fragile than previously thought.

The U.S. credit markets have fallen into a dangerous (fallacious) complacency risking a crash.

The ‘zombie problem’ of the U.S. corporate sector may be smaller than feared.

There has been a lot of speculation on the surprising strength of the U.S. economy. That is, some analysts have speculated that because the U.S. economy has not buckled under the (much) higher and rising interest rates, there could be even “no landing” (not even an actual economic downturn). I and we will contribute to this discussion by conducting an in-depth analysis of the U.S. economy starting here and continuing in a special issue of our GnS Economics Newsletter early next week.

I fear that the hopes for no-landing or even “soft-landing” have been premature and that they have been based mostly on a somewhat superficial analysis on the state of the U.S. economy. The no- or soft-landing arguments can be challenged with just one graph.

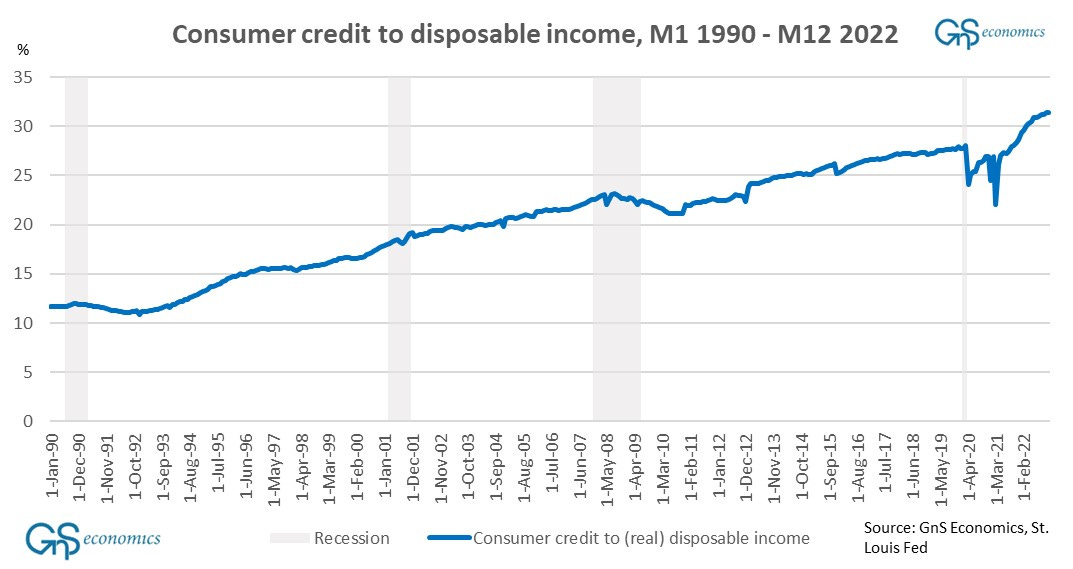

The U.S. consumer credit, basically the backbone of consumption now as houses cannot be used as ‘piggy banks’ for consumption because their prices are falling (see, e.g, the S&P Case-Shiller home price index), in relation with disposable income is at all-time high. Its very rapid rise after the Corona-lockdowns has carried the U.S. economy, but rising interest rates will, eventually, hit hard to over-indebted households forcing them to cut their consumption pushing the U.S. economy into a recession (we return to this in more detail in the Special Issue).

An in-depth analysis of the U.S. economy, of which first part I present here, not just de-bunks the no-landing argument, but essentially turns it into a hard-landing -argument. Please note that as a subscriber of GnS Economics Newsletter, you also gain access to all entries in my personal newsletter.

Banks are ok, aren’t they?

The situation in the U.S. banking sector has taken a rather dramatic turn for the worse.

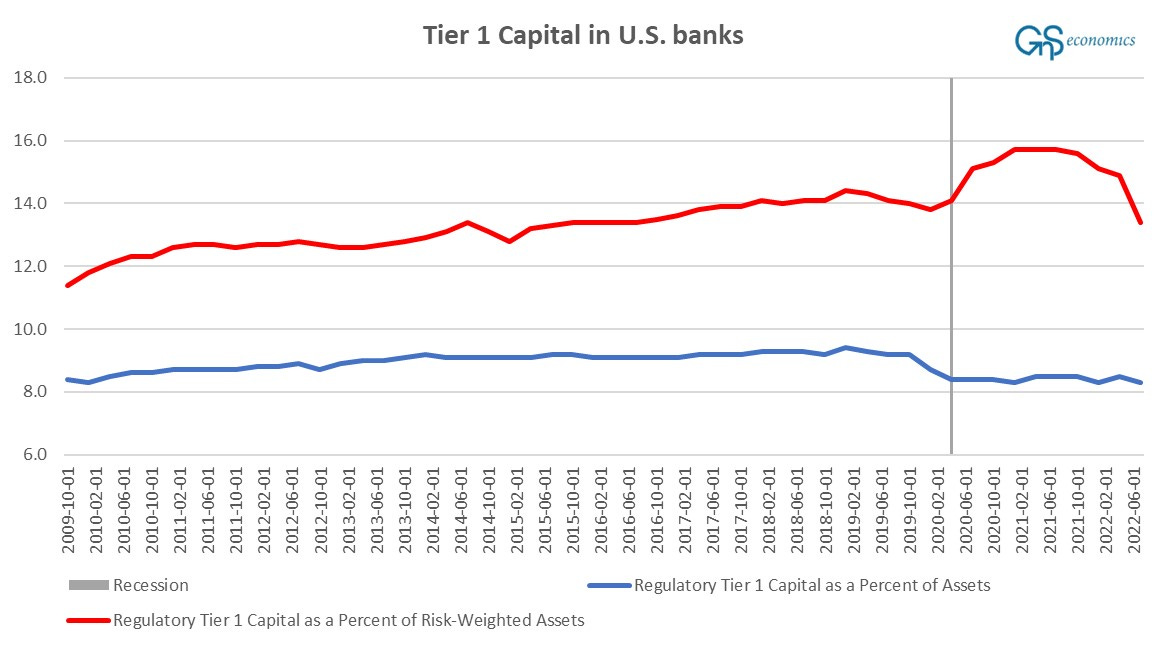

During the Corona-shock of 2020, the most safe capital banks have, the regulatory Tier 1 capital (equity capital and disclosed reserves) as a share of assets, declined below the level of the last quarter of 2009, that is, below the level right after the GFC and the recession that followed. The regulatory Tier 1 capital as a share of risk-weighted assets (all the assets the bank holds that are systematically weighted for credit risk) is still clearly above the late-2009 level, but during the past year, it began a steep decline and it was below the pre-pandemic level already in Q3.

The former implies that the Corona-shock of early 2020 led to either increase in the assets of banks and/or the decline in their Tier 1 capital. The latter, i.e., the jump in the share of rish-weighted assets to Tier 1 capital after the Corona-shock implies that the riskiness of assets banks held declined notably right after the shock, which was complete reversed by Q3 past year. Considering what happened during the Corona-shock and the bailout that followed, we can deduct the following.

As withdrawable, interest-bearing deposits (excess reserves) in the central bank are assets to banks, the massive three trillion USD bailout operation of the Federal Reserve (QE), during the spring of 2020, forced excess reserves to the banking sector dropping the share of Tier 1 capital to assets. On the other hand, it also looks that the bailout altered risk-weights (credit ratings) of different assets in the balance sheet of banks. This was probably a result of different loan guarantee programs run by federal agencies in 2020, which wound down in 2021, and the support of the Fed to corporate credit markets (QE). However, banks also extended a vast amount of loans especially to corporations. The risk-weight of all loans, including corporate loans and mortgages, may now be deteriorating fast in addition to all debt securities banks hold leading to a rapid decline in the ratio of Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets.

Information at hand, however, leaves reason for doubt. We can just speculate what were the drivers of the decline in the share of Tier 1 to assets (both risk-weighted and overall). Yet, the fact remains that U.S. banks are less capitalized than they were prior the pandemic. Thus, the U.S. banking sector has been turning fragile and its likely to continue doing so, when the downturn truly hits.

Credit markets on a waiting pattern

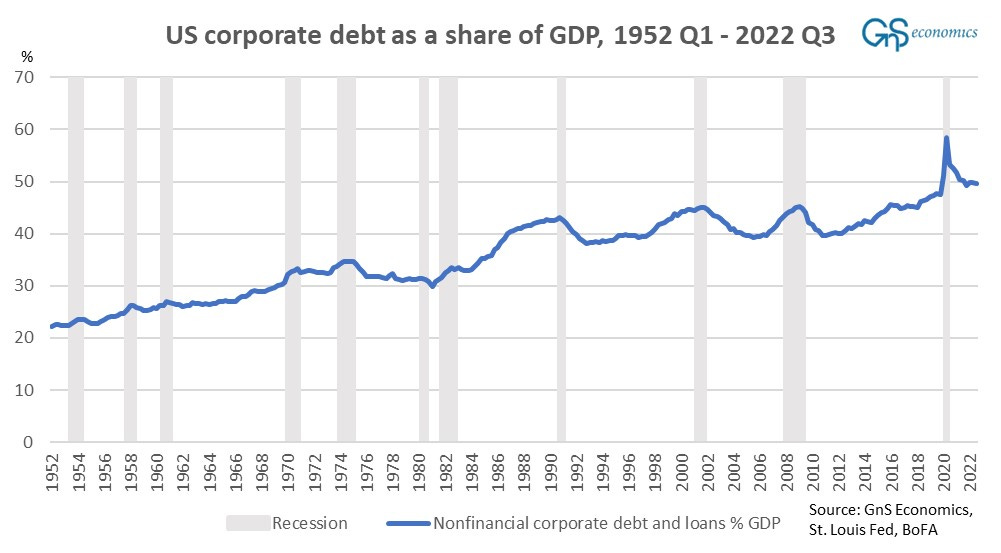

Also U.S. corporations are more indebted than ever before.

Naturally the historical upward trend can be explained partly by development of finance and capital markets, which has made it more easy for companies to acquire and roll-over their debt. This, however, does not change the fact that higher interest rates mean higher debt service costs, which will start affect the investment and consumption decisions of U.S. corporations immediately the economy (consumer) hiccups, if it has not already.

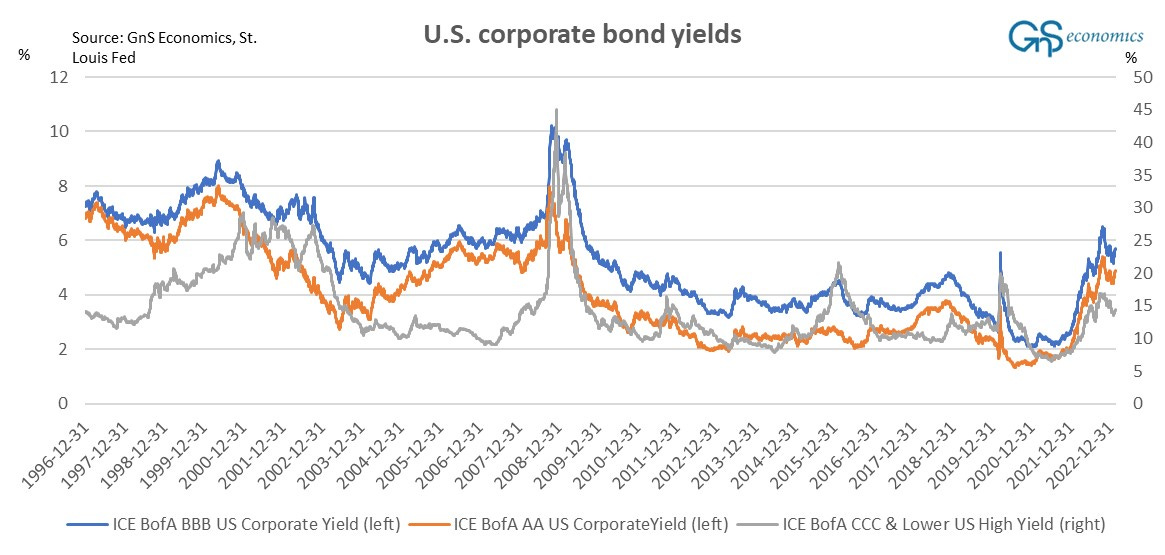

Relating to this, the corporate bond yields tell an interesting story.

Unlike during the GFC and any other economic shock or a hiccup during the past 15 years, yields of high yield, or “junk”, bonds have reacted, proportionally, least mildly to the current tightening cycle. This implies that, for some reason, U.S. investors have remained ‘risk-loving’ at least until recently.

Such complacency can be considered to arise from the general assumption that the Fed will save the credit markets, no matter what, and that the Federal government will keep corporations afloat like they did during the Corona lockdowns. These, however, can be a dangerous fallacies.

The question is, would the Fed truly enact another nationalization of the credit markets in a recession with fast inflation and with its losses accumulating by the day? Republicans currently control the House and there’s a growing fraction within the party demanding return to a more market oriented economy. With the interest payments of the federal government rising rapidly, accumulation of further losses through the Federal Reserve can (is likely to) become a major political issue, when the recession hits and the already large budget deficit starts to grow again.

It’s thus unlikely that the Fed would want or even could take such a massive role in the financial markets than it did during the spring of 2020. This, quite straight-forwardly implies that the U.S. credit markets will be in a heightened risk of an outright crash, when the downturn truly hits.

Zombies that weren’t?

We have been among the most vocal critics of the ultra-easy monetary policies warning, repeatedly, on the possibility of easy credit conditions and ultra-low interest rates breeding “zombie-corporations” (see, e.g., this, this and this). That is, the creation of companies who survive only through cheap debt.

Zombies were introduced to the economic jargon by Ricardo Caballero, Takeo Hoshi and Anil Kashyap in 2008, when they described the unproductive and indebted yet still operating firms in Japan as "zombie companies". They found that, after the financial crash of early 1990s, large Japanese banks kept money flowing to otherwise insolvent borrowers, aka zombies. The reason for this was that these large banks were itself in dire straits, and they wanted to avoid further losses.

However, it looks that the situation in the U.S. at least is not so dire what comes to the share of zombie companies as previously thought. For example, Goldman Sachs Research stripped the newborn high growth companies from the generally used metric used to identify zombie corporations (interest coverage ratio below one) to found that the “zombie infestation” of U.S. credit markets would be much less severe than previously thought (around 4% of the U.S. listed companies would classify as zombies). In July 2021, Giovanni Favara, Camelia Minoiu, and Ander Perez-Orive had came to a similar conclusion in a research published in the Notes of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

This makes sense in the way that U.S. banks nor investors have not been in such dire straits that they would have felt the need to keep companies from failing, what happened in Japan during and after the financial crisis of the 1990’s. This would also partly explain, why yields of junk bond have reacted so mildly, proportionally, at least till now.

While the number of zombie corporations in the U.S. may be lower than previously feared, it does not remove the high likelihood that ultra-easy monetary policy has created weak corporations with high indebtedness poised to fail in a recession. Moreover, it does not guarantee that U.S. banks, now as they are turning more fragile, would not start to support “zombification”.

Conclusion

We can conclude that the U.S. economy is both in a worse and better shape than many analysts have thought. The zombie corporations -issue may be less pressing than previously feared, but the situation of U.S. banks is likely to be worse than previosly thought. Investors at the credit markets are also likely to be ‘sleep at the wheel’.

All-in-all situation in the U.S. economy is worrying. The recently-touted resilience of the U.S. economy looks to be based on false premises and the inability to identify the fracture lines in the banking sector, credit markets, but also in the economy in general. We will deal with the fragility of the overall economy and the timing of the recession in more detail in the forthcoming Special Issue.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.