From Tuomas Malinen’s Forecasting Newsletter.

Issues discussed:

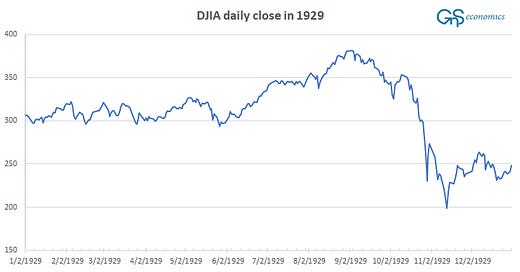

The process of the stock market collapse at the end of October 1929, explained.

There’s a striking similarity in economic and financial conditions that led to the ‘Great Crash’ vs. now.

Commercial banks have enacted “shadow QE”, which has been increasing liquidity (money) in the U.S. economy.

In this second installment of the series mapping the road of the U.S. economy into the Great Depression, I will detail the stock market collapse of late-October 1929.

The timeline and specifics of the crash are from The Great Crash 1929, by John. J. Galbraith. The book, by one of the most famous economists of all time, brings great fervor and detail into the actual process of the collapse. I recommend you read it, if you want to gain more insights on the crash and the reasons behind it. I also urge you to read my previous entry, if you have not already, before you enter this one, as this will continue directly from where it left off. Now, to the crash.

The Great Crash

The first hints of a slowing economy came in July 1929, when the index of industrial production of the Fed dropped (there were, e.g. no quarterly earnings reports). From then on, several other indices, including steel production and freight-car loads, started falling. The mix of bad news and rising interest rates foretold an upcoming recession, and the markets started to drift downwards.

In a few days, the rising volume of trading swamped the brokerage firms. Margin calls, where the value of the stock held on margin by the recipient had declined to a point where it was no longer sufficient collateral, became more frequent and the stock ticker, transmitting stock price information over telegraph lines across the US, started to run behind. Tickers running behind was nothing new, but it had almost always happened during a rising market.

On Monday October 21, the ticker started falling behind while prices fell. An uneasy feeling started to spread among investors across the U.S. If the prices were to fall dramatically, and the ticker were to be seriously behind, there would be no way of telling how much you had lost. Later that day, Professor Irving Fisher of the New York University (NYU) said that the decline in the market had been just "shaking of the lunatic fringe". On Tuesday, Charles E. Mitchell, a well-known American banker, stated that the "decline had gone too far". But, these heavy guns of Wall Street did not stop the downdraft, and Wednesday 23rd was another day marked by heavy selling.

On Thursday, October 24th, the U.S. stock market opened in an unspectacular fashion, but with heavy trading volumes. Prices hovered for a while, but then started to fall rapidly, and the ticker started to lag behind. Price declines kept accelerating and the ticker fell further behind. The pace of sell orders grew at increasing rate, and by eleven o'clock ferocious selling had gripped the market. A few selected quotations given by the ticker showed that the current values were far below the now seriously lagging tape. An overwhelming number of margin calls rolled in and many investors were forced to liquidate their holdings. Increasing uncertainty made investors even more scared and the selling turned into a full panic. The frenzy of selling could be heard outside the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), where crowds started to gather. The police commissioner dispatched a special police detail to Wall Street to ensure peace. Crowds also formed outside branch offices of the stock exchange throughout the country. Then, a savior arrived.

At noon, reporters learned that several notable bankers had gathered at the office of J.P. Morgan and company. Thomas Lamont, a senior banker at Morgan met with the press. He stated that there had been "a little distress selling" at the Stock Exchange due to the "technical condition of the market". At one-thirty the vice-president of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), Richard Whitney, appeared at the trading floor and started making large purchases of different stocks. This carried a clear message: the bankers had stepped in. The effect was imminent. Fear vanished and markets rallied. The flip side of this was that, because the stock ticker was hours late, many had already sold everything with a deep discount on the closing value. This took a serious toll on the psyche of ordinary citizens across the country.

On Friday and Saturday, the volume of trading was heavy, but prices held up. During the weekend there was a massive relief. Disaster had been avoided, and the actions of the bankers were praised. Several noticeable financial, business and political figures went on the press stating the "business situation and the economy is sound". Then came Monday.

On Monday October 28th, the market opened to an uneasy tranquility, which was quickly broken. Selling started, accelerated and by noon the market was in a grip of relentless selling panic. Bankers gathered, but a savior was never seen on the floor of the NYSE. Heavy selling continued through the day. After the stock market closed, there was still no word from the bankers or from anyone for that matter. During the night, panic spread throughout the nation.

On Tuesday, October 29th, selling orders flooded the NYSE at the open. Prices plunged heavily from the start, which fed the panic. Sell orders from all over the country overwhelmed the ticker and sometimes also traders. During the day, massive blocks of stocks were sold, which hinted that the "big players" (banks, investment funds, etc.) were liquidating. At times, there were countless sell orders, but no buyers. This meant that during those times the market was in complete free-fall. There was a brief rally before the end of trading, but despite it Black Tuesday became one of the most brutal days in the history of the NYSE with the DJIA falling by 11 % on heavy volume.

The Aftermath

Within a week, from October 23rd to October 29th, the DJIA lost 29% of its value, but the worst was still to come. From the peak (3rd September, 1929) to through (8th July, 1932) the DJIA fell over 89%. It all but decimated the wealth of both the rich and poor who had invested in the stock market. Yet, the immediate aftermath of the stock market crash was relatively controlled. After the crash, the Fed provided ample extra reserves (loans) to New York banks. The fact that prices of stocks stabilized, made some even argue that the stock market had not actually been in a bubble. The economy also seemed to stabilize through the year-end.

The Great Depression did thus not start right after the Great Crash (a general misconception), but the crash struck a serious blow to the psyche of households, corporations and investors. This surely deepened to economic contraction, which was already ongoing (according to the NBER, U.S. recession started in August 1929). Consumption never recovered from the crash, and continued to fall in 1930. There was a brief hope for a recovery in early 1930, but then in October 1930 Midwestern states were hit by cascading bank runs and failures, starting the Great Depression.

What makes the historical example of the Great Crash relevant are the similarities we are seeing now.

Are we about to repeat the Great Crash?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to GnS Economics Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.