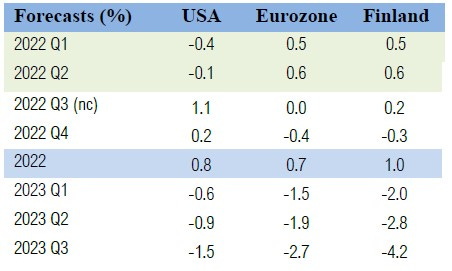

Forecasts

(GnS Economics, OECD, Q-to-Q): Nowcasts are anticipating that the GDP grew relatively decently in the U.S. and in Finland in Q3, while GDP growth would have stalled in the Eurozone.

Manufacturing and services indexes (see below) imply that the onset of a global recession is near. We expect it to begin in Q1 next year. We also expect that the troubles in the European banking sector will re-emerge in December or early next year the latest.

China stimulus

Now we’re talking! The aggregate financing to the real economy increased by fastest-ever September-pace, in September.

Beijing is definitely stimulating now, and we are clearly above the 2021 level in the pace of aggregate financing. But, there seems to not have been a clear direction in stimulus since early this year. What has made forecasting the Chinese stimulus difficult, has been the ‘mismatch’ in communication from Beijing and the actual events in the financial sector (realized level of stimulus).

Thus, we have to wait and see was this just a one-off bounce or a start of an upward trend in stimulus.

ECONOMIC INDICATORS

United States, October (September)

Richmond Fed manufacturing: -10 (0)

Empire State manufacturing: -9.1 (-1.5)

Dallas Fed manufacturing: 6.0 (9.3)

Manufacturing PMI:[1] 49.9 (52)

Service PMI: [2] 46.6 (49.3)

Consumer Confidence:[3] 102.5 (107.8)

Eurozone, October (September)

Manufacturing PMI:[4] 46.6 (48.4)

Service PMI:[5] 48.2 (48.8)

China, August (July)

Caixin manufacturing PMI:[6] 48.1 (49.5)

NBS manufacturing PMI: 49.2 (50.1)

Caixin service PMI:[7] 49.3 (55.0)

THE OUTLOOK

The global manufacturing and services outlook starts to look rather grim. The United States, the Eurozone and China all seem to be in contraction, on which we warned in spring. If we look at the new export orders, in many countries they are in a state of outright collapse. Global recession is thus almost here.

The most acute risk of a banking crisis seem to have passed, but most likely only for a short-while. On Thursday, Financial Times reported that Credit Suisse was to re-organize and recapitalize its operations.[8] These included a $1.52 billion capital injection from the Saudi National bank and a campaign to raise over $4 billion worth of capital. Moreover, Credit Suisse announced that it will sell parts of its securities production ‘arm’ to investment groups PIMCO and Apollo. As Credit Suisse was the main culprit considering the risk of a new banking crisis in Europe, this eased the threat of such an event somewhat. However, problems have not gone anywhere.

And, we came really close to the collapse of the financial system. On September 28, the Bank of England stepped (back) into the gilt (U.K. bond) markets and started buying government bonds with longer maturities to stop the collapse in their value. This was done, because pension funds were faced with major margin calls, which threatened to cause a rapidly cascading run on their liabilities, as trust in their liquidity and solvency would have become questioned. A financial crisis erupting in one of the financial hubs of the world (London) combined with the troubles of Credit Suisse would have created a very toxic combination most likely leading to an unravelling of the financial system.

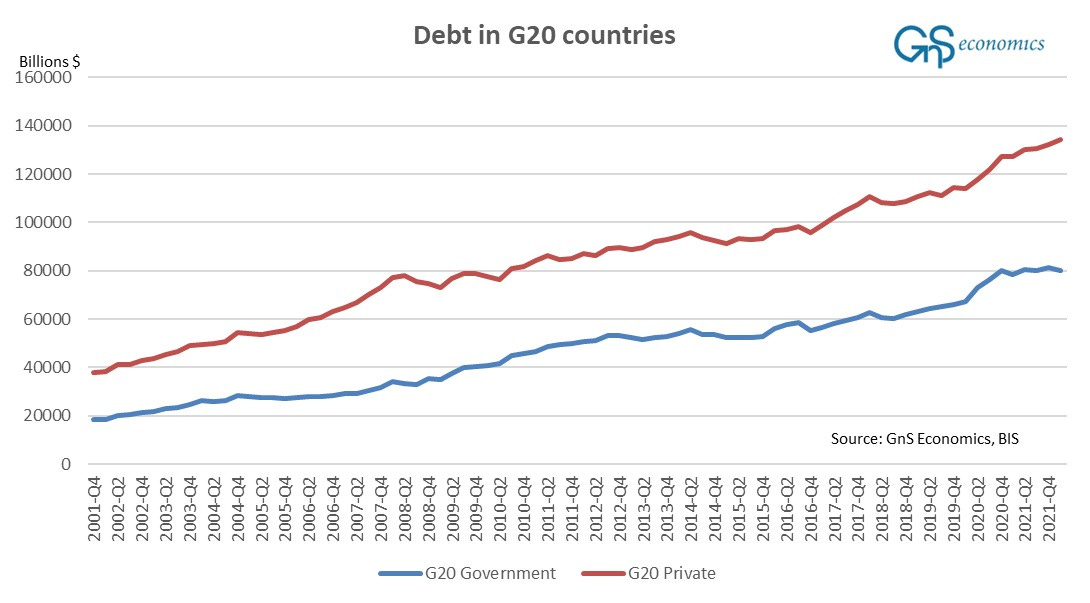

These issues have not eased, because we are now threatened by a debt crisis. Figure below presents the debt levels of G20 countries. Both private sector and general government debt have grown rather relentlessly in recent years, while the growth of government debt has eased since leaping massively in 2020 and 2021. In Q1 2022, the debt-to-GDP ratio of government and private sector debt stood at quite worrying 262%.

However, the picture becomes even more grim, when we turn to the countries that caused the 2010-2012 European debt crisis. Their sovereign debt-to-GDP ratios are presented in Figure below. While they have eased from their highs in 2020-2021, they are still clearly above the levels that led to the crisis in 2010-2012.

Rapidly rising interest rates are thus becoming a problem also in the industrialized nations instead of just causing issues to indebted emerging market economies. Unsurprisingly, problems are most pressing in the euro area.

When the debt crisis truly started in September 2010, the Italian 10 -year bond yield was around 3.8%, the Greek bond yield was at around 5%. The Spanish bond yield was around 3.3% and the Portuguese 10 -year bond yield was around 4.7%. Now, they are around 4.6%, 5.2%, 3.3% and 3.5%, respectively. Alas, the former crisis countries have more debt, interest rates are higher than in 2010 and they are poised to rise further. It’s rather difficult to imagine any other outcome to this than another debt crisis.

The pressing question is, what will European authorities do next?

It is quite interesting that the discussion on the “energy crisis fund” has all but stopped. This may be, at least partly, due to the ‘close-call passing’ of the Recovery Fund in Finnish Parliament in May 2021, and the discussion surrounding it, which led, e.g., Valdis Dombrovskis, an Executive Vice-President of the Commission and the Commissioner for Trade, to tweet, right before the Finnish Parliament voted on the Recovery Fund that it would be “one-off” and “unique”. Still, it’s likely that a proposal for an ‘energy fund’ will eventually come, but it will be already late (passing of the Recovery Fund in all member states took a year). Moreover, its passing in Finnish Parliament is far from guaranteed.

So, the question becomes, what will the ECB do, and that is an open question. Tuomas Malinen has speculated on it on his newsletter, freely available to all Deprcon subscribers.[9] He will also continue with this topic this week by going through the implications of all this to global market liquidity.

While we revoked the warning for an imminent banking crisis, the threat has not gone away. Sovereign debt crises are almost always tied to banking crises, because for example sovereign bonds are used as collateral in banks. The Federal Reserve keeps on providing massive amounts of liquidity to Swiss National Bank through a dollar-swap line. This implies that the problems of Credit Suisse and possibly other Swiss banks are far from over.

If (when) a debt crisis emerges in the Eurozone it will most likely be accompanied by a banking crisis. And, as the debt crisis may flare-up practically at any moment, we urge everyone to keep preparing for the banking crisis, even though the imminent threat has passed, for now.

[1] Values above 50 indicate growing output, while values under 50 indicate declining output. Figures were obtained from TradingEconomics.

[2] From TradingEconomics.

[3] The Conference Board.

[4] From TradingEconomics.

[5] From TradingEconomics.

[6] From TradingEconomics.

[7] From TradingEconomics.

[9] Just email us to: contact@gnseconomics.com with details of your current Deprcon payment plan to gain access.

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current as at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry and the information contained in this post may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. Readers should always consult their own personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and readers using this post do so solely at their own risk. Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial or other consequences of their actions. GnS Economics nor Tuomas Malinen cannot be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.