I am going to continue on China today. Some commentators and analysts present China as something of a marvelous economic powerhouse. This is a general misunderstanding. The true nature of Chinese “economic miracle” is revealed, if we scratch the surface a bit. The Chinese economy has been growing rapidly, though.

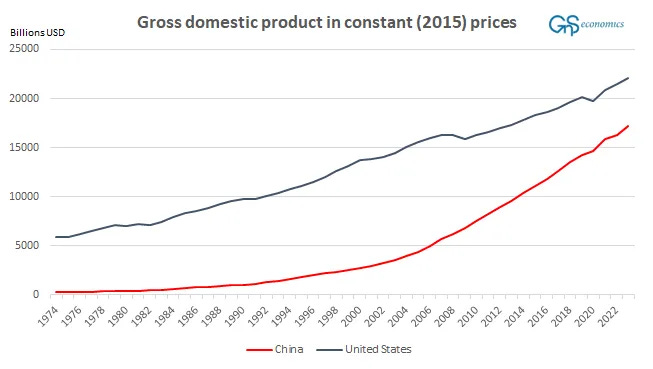

The figure above presents the gross domestic product, or GDP, of China and the U.S. in constant 2015 dollars. What this means is that the GDP is calculated using observations of one year, in this case 2015, as a base-year (“constant”). That is, 2015 is the year all the other observations are related to. In standard indexing, 2015 would have the value 100 and all other (yearly) observations represent a change in the GDP in relation to that year. If GDP would grow by 2% in 2016, its value would be 102. If GDP would have been 3 percentage points smaller in 2014, its value would have been 97. This is done to remove the effect of price increases (or decreases), i.e., inflation (deflation) from the series. If production of a country grows by 1%, but prices increase by 2%, calculation of GDP in nominal prices would show it to have grown by 3% even though the production of a country would have grown only by 1%. Indexing of the series removes this, because everything is presented in relation to the base year (2015). We do not thus observe the changes year-per-year, but changes with respect to the base year (2015). You can find a more technical explanation of indexing, e.g., from St. Louis Fed.

Essentially those who argue that the Chinese economy would already be larger than that of the U.S. are using either GDP series with current prices, which are inflated (by inflation), or the so-called purchasing-power-parities, or PPPs, which try to mimic the “actual” differences in consumption of goods and services between countries. Some consider this to be relevant for the economic prosperity comparisons, because people in countries with different level of economic development consume different products and services, which leads to differing prices between countries (see, e.g., Capital Economics for an attempted explanation).

I’ve been looking at GDP series for two decades, and I use only constant prices in such comparisons nowadays. This is because, by indexing the series you fix your reference point, which essentially eliminates the effect of currency manipulation (through FX-rates or inflation). Constant GDP is a measure of what is actually happening in the economy, while PPP-adjusted GDP series are subject to all kinds errors and manipulation. It’s practically impossible to try to find the correct prices of (practically) all the products of an economy required for PPP calculations. Here’s a good IMF piece going through the pros and cons of PPPs.

Yet, all the above becomes irrelevant, when we start to measure, what’s the actual difference in the standard of living of populaces in China and in the U.S.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to GnS Economics Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.