On Friday, the largest market liquidation in crypto-market history occurred after President Trump posted on social media, threatening China with 100% tariffs. Some investors lost their whole portfolio before Mr. President reversed course with a social media entry downplaying the risks.

Those who lost their life savings in yet another crypto-carnage could blame President Trump, and you would be correct, partially. Yet, this figure presents the primary reason we’re here.

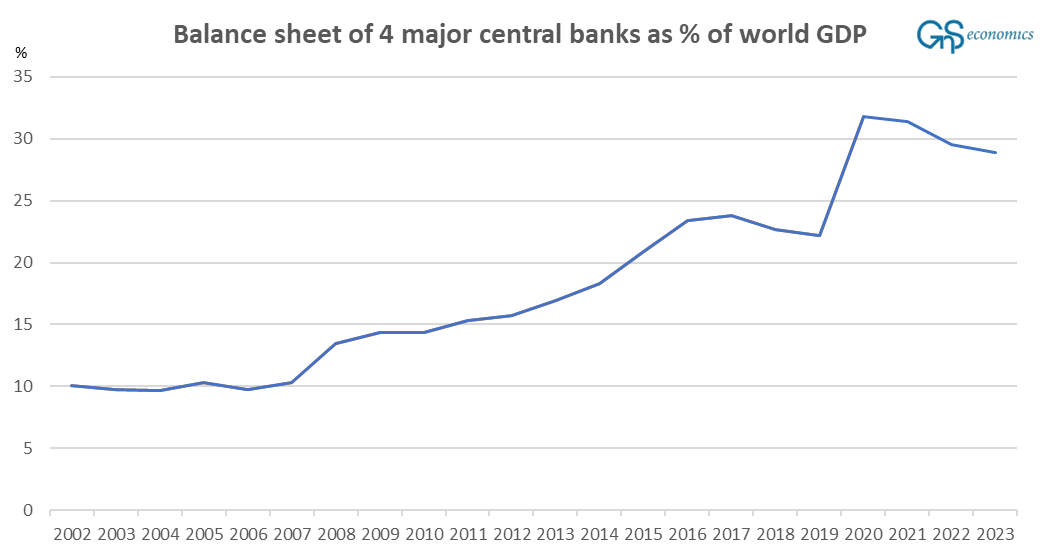

I have not really cared to update the graph anymore, but due to the asset roll-off of the Federal Reserve, the share has most likely dropped a bit (see the share that includes all major central banks). That is also not the main point here, but what happened before 2021.

For a very long time, the assets (securities) held by the central banks grew modestly. Unless there was a crisis, the assets usually were below 10% of GDP. Not anymore.

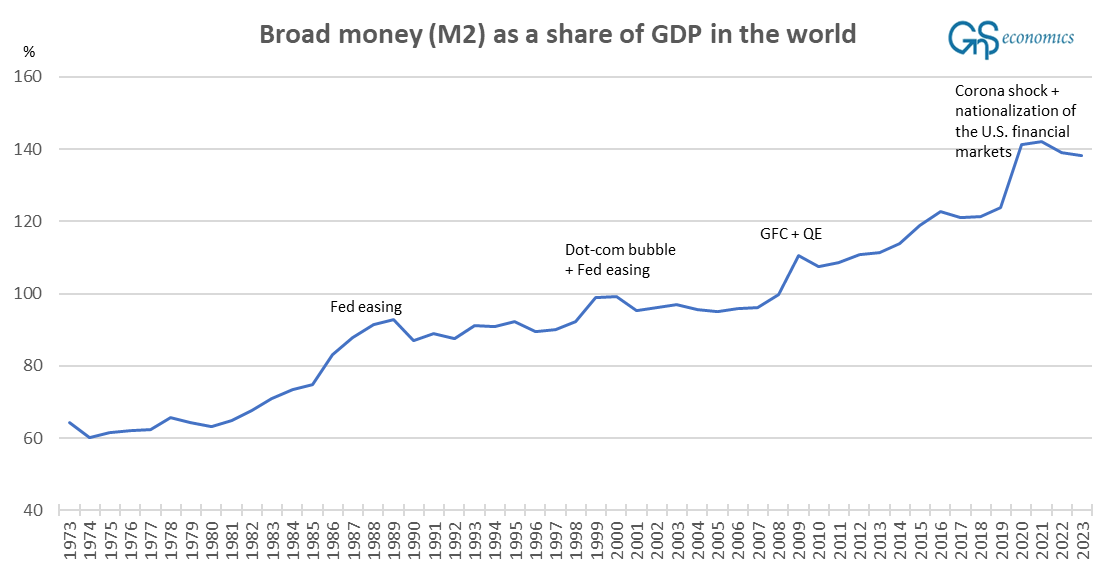

The monetary meddling of the central banks after the GFC led to a massive increase in the money in circulation. This is the most update data on M2 money (“broad money”) in circulation in the world.1 I’ve added a few key policy actions to clarify the message conveyed by the graph.

After the dismantling of the Bretton Woods system, where currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, which was pegged to gold, between 1971 and 1976, the amount of money has grown rapidly. The first “Fed easing” shown in the figure refers to the Federal Reserve’s decision to lower interest rates after the shock delivered by Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, which was enacted to curb the runaway inflation caused by the oil shocks of the 1980s. Interest rates in the U.S. reached their peak in the vicinity of 20% in June 1981, after which they were cut to under 10% in two years.

The Dot-com bubble, its implosion, and the lowering of the interest rates from 6.5% to less than 2% in just a year by Fed Chair Alan Greenspan delivered another impulse to the supply of money. However, the major turn came in the Great Financial Crisis and the quantitative easing (securities purchase programs) launched after. They transformed central banks into active participants not only in money creation, a traditionally exclusive role for commercial banks, but also in the markets. I have detailed the (detrimental) effects of these policies in two Epoch Times articles (this and this).

However, the most significant shock came in the spring of 2020. From my Epoch Times piece:

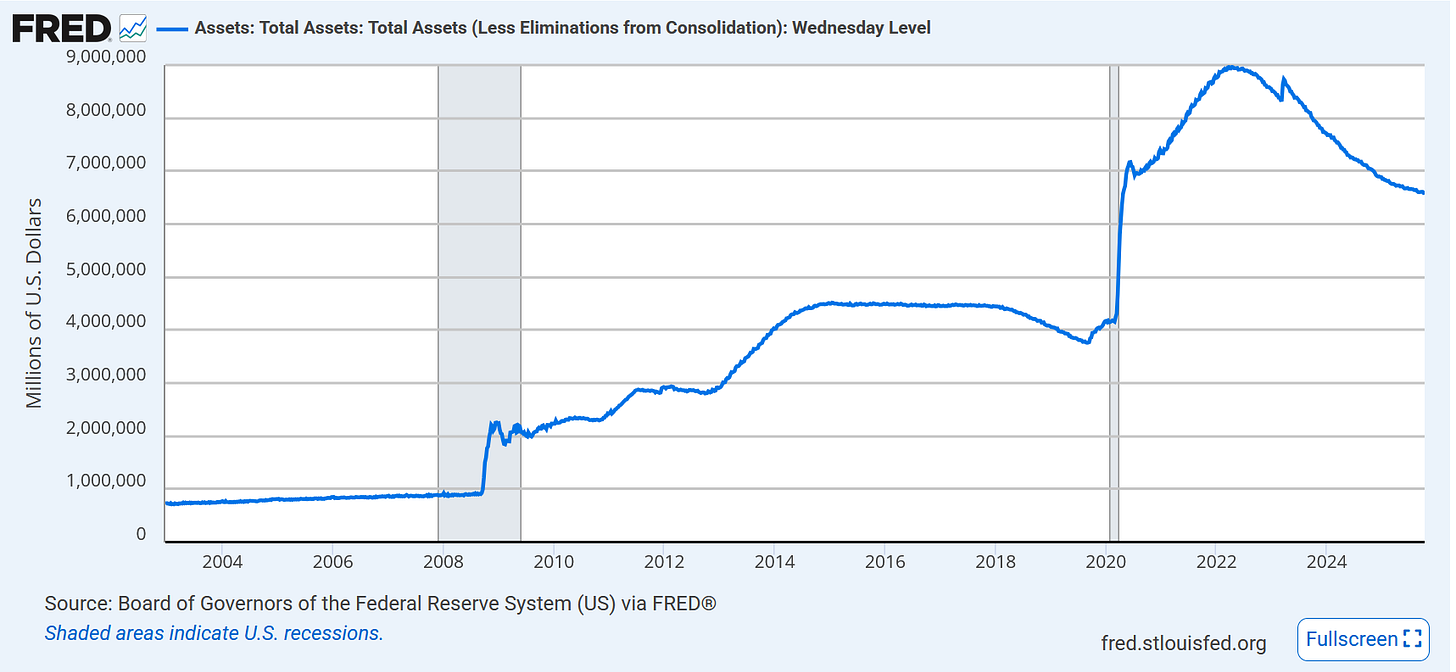

In March 2020, the coronavirus outbreak was freaking out the markets, and on March 16, 2020, they crashed. The volatility index reached 82.69, the highest on record. The Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged by 2997 points, or 12.9 percent—the worst point drop on record.

On the 16th, the New York Fed announced that it will add $500 billion in the over-night loans to repo-market. On the 17th, the Fed announced that it would use $1 trillion to mob up corporate paper from issuers. On the 18th, the European Central Bank announced that it would buy 750 billion euros worth of bonds and securities. On the 19th, the Fed announced that it would create lending facility to money market mutual funds. On March 25, 2020, interest rates of short-term corporate debt surged to 2.43 percent above the federal-funds rate, the over-night lending rate of the Fed, which led the central bank to issue a program targeted at the corporate markets.

At the end of May 2020, the Fed backstopped “repo” and U.S. Treasury markets, intervened in corporate commercial-paper and municipal bond markets and short-term money-markets, and bought corporate bond ETFs, including some speculative-grade, or “junk,” corporate debt. It also launched its “Main Street Lending” program, where it provided loans to middle-market businesses. Alas, come June 2020, the Fed had become the financial markets of the United States. The bailout operations enacted by Greenspan had reached the point where the fears that the creation of the Fed would ‘socialize’ the economy had materialized.

So, yes, you lost your money, partly because of the reckless tweeting of President Trump, but mostly because central banks have become active players in the economy, printing massive amounts of money, destroying the risk-and-reward relationship. This is how enormous bubbles form, and they will eventually burst.

The main takeaway from the above is that central banks will, most likely, uphold the bubble by any means necessary, because if they did not, their credibility would be shattered. While many market commentators are currently (still) celebrating the rally, it would not take long for them to identify the true culprits behind the “exuberance,” that is, the central banks. The outcome would, (again) most likely be the end of the modern central banks, and while I would welcome such a development, many are very afraid of what it would imply (more on that later).

President Trump has also made some egregious comments regarding the war in Ukraine. While many in the MAGA movement continue to glorify him, I think he’s losing control, of everything. I will return to those tomorrow.

Tuomas

Disclaimer:

The information contained herein is current at the date of this entry. The information presented here is considered reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Changes may occur in the circumstances after the date of this entry, and the information contained in it may not hold true in the future.

No information contained in this entry should be construed as investment advice. Neither GnS Economics nor any of the authors can be held responsible for errors or omissions in the data presented. Readers should always consult their personal financial or investment advisor before making any investment decision, and those using this post do so solely at their own risk.

Readers must make an independent assessment of the risks involved and of the legal, tax, business, financial, or other consequences of their actions. Neither GnS Economics nor any of the authors can be held i) responsible for any decision taken, act, or omission; or ii) liable for damages caused by such measures.

The views of Tuomas are his own. They may or may not be endorsed and supported by the partners and staff of GnS Economics.

Explanation from the IMF:

Broad money is the sum of all liquid financial instruments held by money-holding sectors that are widely accepted in an economy as a medium of exchange, plus those that can be converted into a medium of exchange at short notice at, or close to, their full nominal value. This indicator is expressed as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) which is the total income earned through the production of goods and services in an economic territory during an accounting period.